As with the economy at large, supply and demand are the fundamental dynamics that shape the digital advertising economy.

In advertising, “supply” represents ad space in any form. As such, when you hear or see “supply-side” being used in adtech, it refers to technology, solutions and vendors that provide ad space (ie. publishers) or aggregate and facilitate the distribution of ad space (ie. SSPs/exchanges). This is why supply-side platforms (SSPs) are named as such. Note that the term “sell-side” is interchangeable with supply-side.

“Demand” on the other hand, refers to advertisers’ demand for ad space. Practically speaking, this demand translates to ad budgets. In this context, consumers are the advertisers with ad budgets. Hence when you hear “demand-side” being used in adtech circles, it refers to technology and solutions that are deployed by advertisers or their agencies to purchase digital advertising inventory. This is why demand-side platforms (DSPs) are named as such. Note that the term “buy-side” is interchangeable with demand-side.

In adtech, many of the core platforms facilitate transactions between advertisers and suppliers by aggregating digital ad supply and demand. Sell-side technologies help publishers generate more revenue by increasing access to demand. Demand-side technologies help advertisers access more supply while offering improved campaign performance. Both supply-side and demand-side technologies also provide significant improvements in operational efficiency.

However, it’s important to note that on an industry-level, demand aggregators generally hold a more substantial share of market value compared to supply aggregators. There are two primary reasons for this. The first is because ad spend (ie. demand) is the fuel that powers the industry, with advertisers representing the metaphorical sun around which the planets of the industry orbit. No ad spend, no ads. No ads, no industry. The second has to do with the overarching dynamics of the internet economy. Understanding these dynamics means understanding a big part of how the industry works and the incentives at play. To explain this, we’ll borrow from Aggregation Theory.

What's Aggregation Theory?

Introduced by technologist Ben Thompson, Aggregation Theory describes how certain internet-based companies (e.g. Google, Meta) have been able to attain unprecedented market dominance and grow more powerful than any traditional business could pre-internet. Here’s a primer for those new to its concepts.

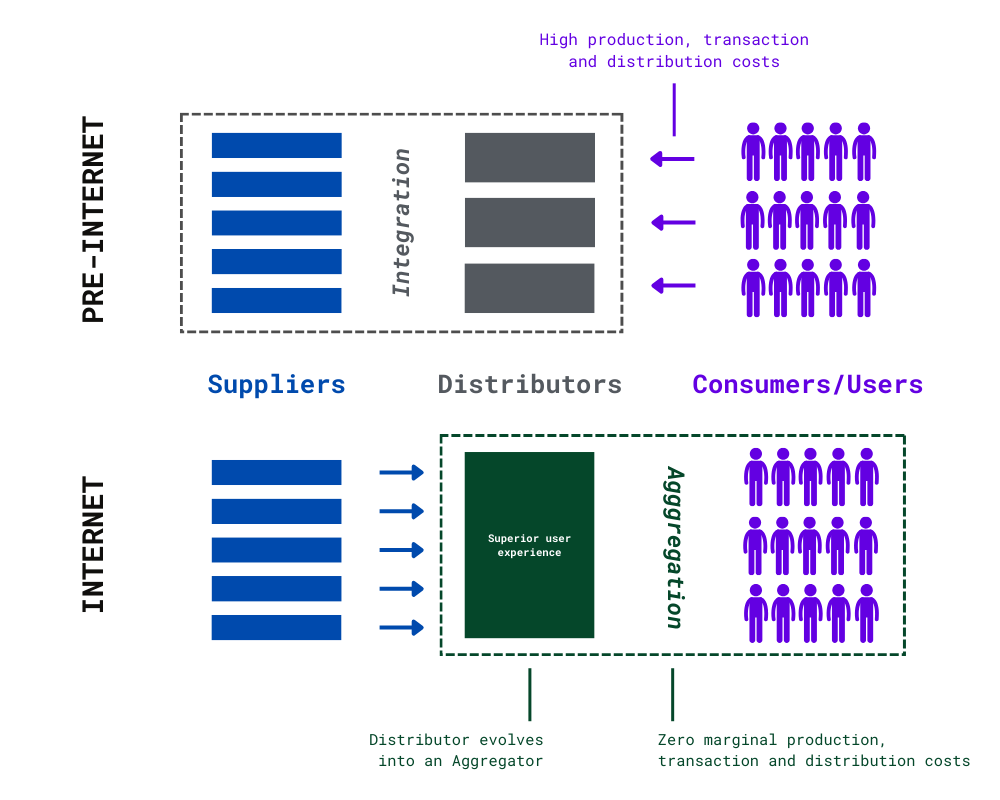

The value chain in any market can be organised into three categories: suppliers, distributors, and consumers/users. Before the internet, businesses often accrued power by vertically integrating control of distribution with control of supply. Examples include newspapers integrating distribution with content creation or book publishers integrating distribution rights with control of authors. Since there are always more consumers than suppliers and because distribution and transaction costs are high in an offline world, this route was more economical and provided more leverage. However, the internet flipped that dynamic on its head. Distribution costs vanished, user acquisition and transaction costs went to zero (think of how trivial it is for Google or Meta to acquire a new user), and the digital nature of goods eliminated marginal cost of production. All of this made it possible for distributors to form direct relationships with end users at a scale far beyond what was possible pre-internet.

The result was a fundamentally different playing field. One where the focus moved away from supplier relationships and towards prioritising consumers/users. This means that the best distributors win and evolve into aggregators by providing the best user experience (note that the definition for a good user experience can vary greatly depending on the industry). This earns them more users, which attracts more suppliers, which then further enhances the user experience, thus creating a virtuous cycle. We call these companies aggregators* because they grow powerful by “aggregating” demand (ie. users/consumers) and connecting that demand with increasingly modularised and commoditised supply.

*The internet has created an abundance of supply (much of which coming from goods and services offered by aggregators). As such, a common starting point for aggregators is helping users sift through supply via discovery and curation.

This dynamic led to pre-internet incumbents such as newspapers and book publishers, who traditionally joined distribution with supply, finding themselves quickly losing value to these aggregators. In addition, the virtuous cycle dynamics described above combined with internet network effects creates winner-takes-most scenarios across many industries, granting these companies leverage and value far beyond what was possible pre-internet.

Applying Aggregation Theory to AdTech

Aggregation Theory is a great explanation for how the internet economy works. As a primary source of funding for that economy, it’s no surprise that its concepts can also be applied to digital advertising and adtech. Here, it makes sense to examine the open web and walled gardens separately given industry dynamics are different for the two.

Open Web – The part of the internet that’s accessible to all advertisers and suppliers and not controlled by any single entity. The internet excluding inventory owned by Walled Gardens.

Walled Gardens – Closed ecosystems controlled by a single company. The controlling company has a fully vertically integrated advertising offering and sets the rules for how content and advertisements are displayed and interacted within its ecosystem.

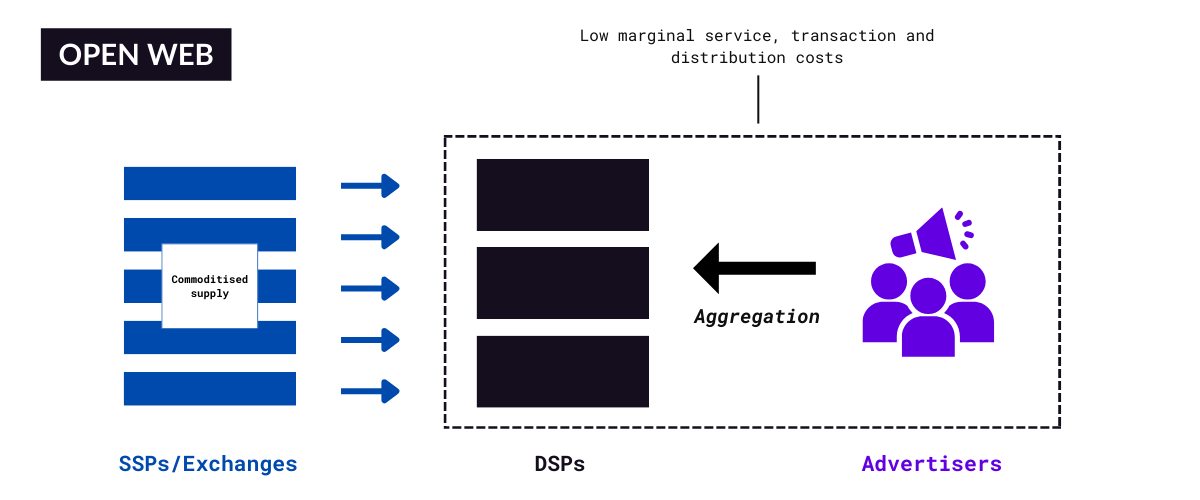

Open Web

By aggregating demand and controlling where ad dollars flow across supply sources, large, global demand-side platforms* (DSPs) hold the most value across open web ad tech. Through the lens of Aggregation Theory, DSPs attract advertisers by providing a superior user experience. This improvement might manifest in various forms: an intuitive UI, access to diverse ad inventory, better campaign results, efficient automation tools, and/or competitive pricing. As a DSP attracts more demand, it generates increased revenue, captures more data, and becomes more attractive for preferred supply sources. These dynamics combined with the diminishing marginal cost of serving additional advertisers allows the DSP to further improve its product. This leads to attracting even more advertisers, thus creating that virtuous cycle. Additionally, internet network effects intensify this process, fostering a competitive landscape where a small number of powerful DSPs emerge over time, dominating the market in a “winner-take-most” scenario.

*Here we’re referring specifically to independent DSPs (ie. DSPs that are not owned and operated by a walled garden).

Supply-Side Platforms (SSPs) and ad exchanges are essential components of the digital advertising ecosystem, yet they generally wield less influence compared to their demand-side counterparts. In addition to the aforementioned advantages of DSPs, supply in the industry has become increasingly commoditsed. The ease with which publishers and individuals can produce content across various mediums has led to an abundance of digital ad spaces. Particularly in the absence of unique, scaled content or data, these medium-to-long tail ad spaces tend to be largely interchangeable in the eyes of advertisers. This situation was compounded by the introduction of header bidding years ago, which enabled publishers to offer their ad inventory to multiple SSPs at once. Consequently, the same ad inventory is often available across various SSPs, diminishing the exclusivity and differentiation that some SSPs might have previously enjoyed. Therefore, not only is there an unprecedented volume of ad inventory available, but it’s also more widely distributed across numerous SSPs. Unlike in traditional offline advertising, where physical constraints limit ad supply, digital advertising faces no such limitations. This abundance and widespread availability of ad inventory significantly erodes the competitive edge that SSPs and ad exchanges might have had based solely on their inventory offerings.

A crude but telling illustration of the value-disparity between adtech demand and supply-sides is that the largest independent DSP (The Trade Desk/TTD) has a market capitalisation of $33.58 billion USD while the largest independent SSP (Magnite/MGNI) has a market capitalisation of just $1.29 billion (as of 11 January, 2024).

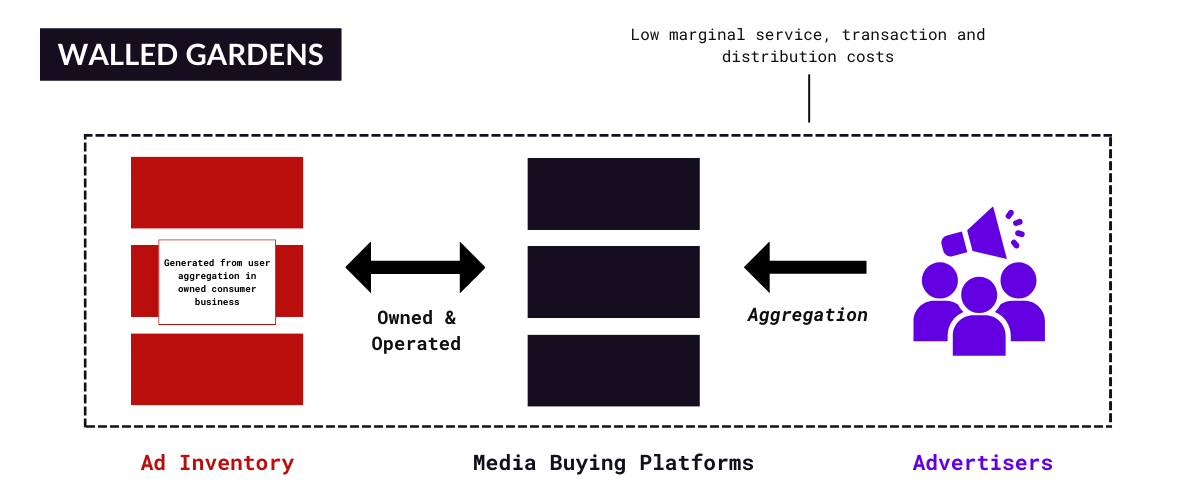

Walled Gardens

Just as Aggregation Theory helps us understand how companies like Google and Meta accrue power in consumer markets, it can also help explain their dominance as walled gardens in digital advertising.

Much like DSPs, walled gardens express the theory’s concepts by creating an appealing and efficacious product to attract and retain advertiser demand. The more ad budget flows through their media buying platforms, the more data these companies gather. This data is then used to improve the performance of their existing features while also helping launch new products, which in turn attracts even more ad budgets. The virtuous cycle is supercharged by internet network effects, further solidifying their position in the market.

The key differentiator for walled gardens compared to DSPs lies in their control over both the demand and supply sides. Not only do they aggregate demand through their buying platforms, they’re able to distribute that demand across a constellation of owned-and-operated supply (ie. web services and apps) via their own infrastructure. That supply, comprised of billions of people globally, positions walled gardens as the most straightforward and cost-effective choice for most advertisers to connect with the broadest swath of their target audience(s).

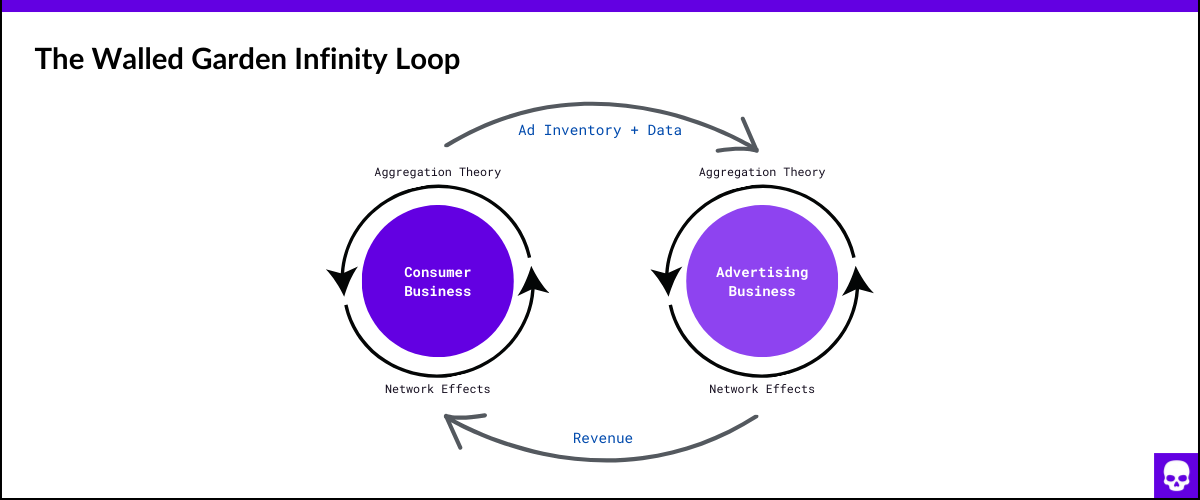

The largest walled gardens also have the advantage of two synergistic virtuous cycles driven by aggregation feeding into one another:

- Aggregation Theory helps explain how they were able to grow the usage of their consumer products and services to billions of people worldwide.

- This vast consumer user base, along with the data generated, effectively forms their ad supply. This is key to making their advertising offering highly attractive to advertisers, thereby consolidating advertiser demand.

- The revenue generated from advertising is reinvested into their consumer business. This investment not only helps in acquiring and retaining users, but also enhances the appeal of their advertising platforms, creating what could be described as a double virtuous cycle, or an infinity loop.

All of this is to say that it shouldn’t be surprising that walled gardens are the most powerful forces in the digital advertising industry. In fact, their dominance is such that they are occasionally the target of government antitrust interventions.

To recap, this entry covered the dynamics of supply and demand and what they represent in the context of adtech, and why market value tends to accumulate on the demand side. While exceptions and nuances exist, grasping these concepts will go a long way in contextualising and understanding the dynamics and incentives that drive not only the digital advertising economy, but the broader internet economy as well.