2023 can be considered the year that machine learning-driven “black box” bidders took center stage in the industry. Led by Google’s Performance Max (PMax) offering, a parade of other platforms followed, each with their own versions of opaque, algorithm-driven media buying products. Unsurprisingly, this has elicited much teeth gnashing within the industry. Concerns regarding transparency, relinquishing control to walled gardens, and platforms grading their own homework were (and still are) rampant. This was mixed with skepticism, cynicism, and even existential dread among advertising professionals. My personal visceral reaction was very much along those lines. Having spent a fair portion of my career on the programmatic buy-side, this direction of travel runs counter to much of what I was conditioned to accept. Like many who got into adtech/programmatic, I was attracted by the chance to infuse creativity into media campaigns by modulating platform technologies. This new wave of products takes much of that away, while also moving against historical industry virtues like transparency and control.

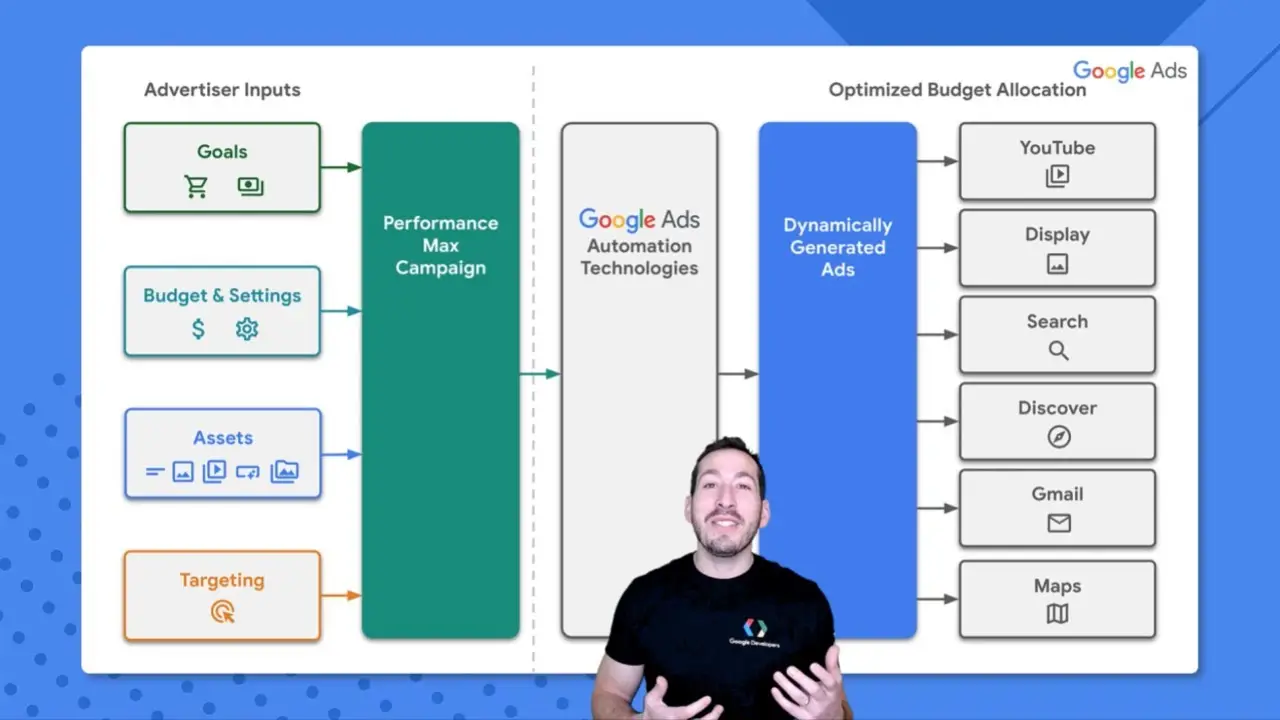

PMax overview diagram (source: Google Ads Developers)

All that said, this development was neither sudden, nor unexpected. Rather, it represents a culmination of the industry’s direction of travel in recent years. This post isn’t to argue for the “rightness” or “wrongness” of this direction, but rather to highlight several reasons why I believe these products are here to stay.

Industry Trajectory

While Google (PMax) and Meta (Advantage+ Shopping Campaigns) are generating the most headlines, other players are following suit with similar offerings in this category. This includes Criteo with Commerce Max, TikTok with Smart Performance Campaigns, and Microsoft with… Performance Max (no seriously, they went with the same name). As mentioned, this isn’t an overnight thing. Adtech platforms have been steadily infusing automation while removing front-end complexity/control from their offerings for years. This holds true even prior to data privacy legislation and the phasing out of third party identifiers acting as an accelerant.

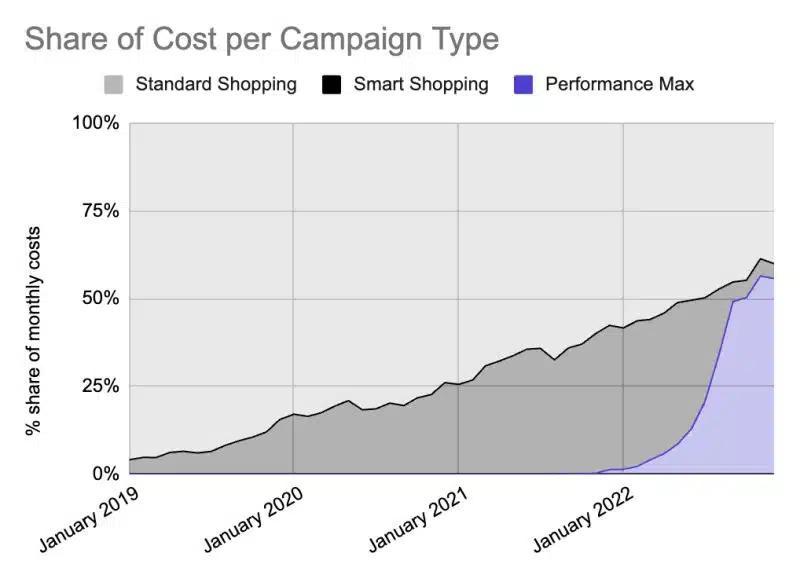

Using Google as an illustration, machine learning was applied to Search and Shopping ads to create Dynamic Search Ads‘ in 2011 and Smart Shopping campaigns in 2018 respectively. In many ways, PMax can be thought of as Dynamic Search Ads + Smart Shopping campaigns. This is underscored by the fact that Google began transitioning existing Smart Shopping campaigns to PMax beginning in mid-2022. The below chart by Mike Ryan & Smarter Ecommerce clearly visualizes this as the inflection point of PMax adoption.

This trend aligns with a broader pattern in technology, where front-end complexity gets abstracted away as products mature. PMax and other black boxes can be thought of as the culmination of that trend, which Google echoed in their latest earnings call (emphasis mine):

We are very please with how Performance Max is performing. It gives advertisers really a maximum performance across all inventory from one really AI-powered campaign, and it's probably the ultimate example of AI in action across our Ads products. It's delivering excellent ROI. Those using it achieve on average over 18% more conversions at a similar cost of action.

Signal Loss Compensation

The introduction of data privacy legislation (e.g. GDPR, CCPA) and the degradation of third party identifiers have resulted in platforms losing a significant portion of the signal historically utilized for behavioral targeting, campaign optimization, and in-channel attribution. As a result, advertisers’ ability to address users and optimize campaigns at the line item level has been greatly compromised. These factors have further accelerated the path towards black box bidders as platforms seek to combat this signal loss, improve advertiser performance, and claw back lost revenue. As stated by Eric Seufert in a post on this topic:

Automation takes on added value for ad platforms, but especially for Meta and Google, in the new privacy environment. PMax and Advantage+ allow these platforms to optimize on-site ad engagement while being blind to the precise consequences of any given ad interaction: because the connection between ad engagement and off-site conversions (eg. purchases made on a website or in a mobile app) is broken, platforms can’t target individuals based on behavioral history.

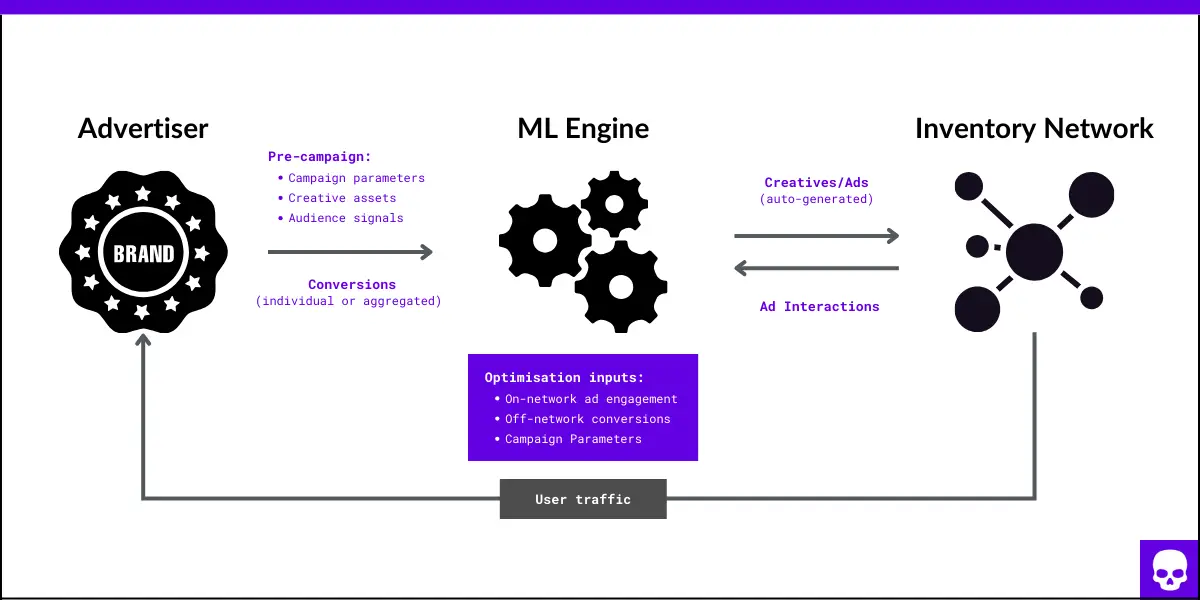

By optimizing creative delivery/rotation across the widest possible inventory surface area, black box solutions allow platforms to maximize bidder decisioning/ efficiency based on on-network (e.g. within Google or Meta properties) interactions while ingesting off-network (e.g. advertiser site/app) conversion signals for comparison. Analyzing on an aggregate level at large enough scales allows platforms to at least partly overcome the signal loss to deliver spend and performance. The diagram below illustrates a simplified version of the mechanics:

Risk Mitigation

For media activation teams operating beyond a certain scale, a large percentage of the job is risk mitigation. The mountains of documentation in place at large agencies to minimize financial and operational error is proof positive. With media buying generally being a low-margin service, one bad incident or overspend can wreak havoc on the P&L. At the same time, there’s a real shortage of talent relative to supply. This is especially true here in Singapore, where every global AdTech player, agency and consultancy has made their APAC headquarters, further diluting available talent. As such, talent churn often outpaces the time/resource required to train folks to become dependable biddable/programmatic practitioners. This means that teams have to do more with less, placing greater emphasis than ever on operational efficiency.

There’s also growing demand from brands for their agencies to offshore media activation headcount for cost-cutting purposes. These days, It’s not uncommon for brands to have agencies default to offshore roles unless sufficient justification can be provided for the headcount to be onshore. No matter how robust the training or detailed the documentation, offshoring always comes with an increase in risk.

Put all that together, and suddenly the idea of ad products that remove complexity, improve operational efficiency, and reduce incident risk while still delivering scale and performance becomes very hard to resist for brands and agencies. And for small/medium-sized businesses that don’t work with an agency and don’t have an in-house media team, the appeal of these black boxes are even more self-evident.

Performance/Efficiency over Transparency/Control

As the trailblazers in this category, the gambit that Google and Meta made is that advertisers would be willing to sacrifice transparency + control for operational efficiency + performance. Based on agency feedback from as far back as late 2022 and the below statement by Mark Zuckerberg on Meta’s Q3 2023 earnings call, it appears that the bet is paying off (even if there are some bumps in the road).

Our AI tools for advertisers are also driving results with Advantage+ Shopping Campaigns reaching a $10 billion run rate and more than half of our advetisers using our Advantage+ Creative tools to optimize images and text in their ads creative.

It’s one of those things where if you ask anyone in the industry whether they’re in favor of transparency and control, the answer will pretty much always be “yes”. That said, my experience is that if push came to shove, most performance advertisers are incentivised to prioritize performance and budget delivery above all else.

This isn’t to say that there haven’t been fervent calls from brands and agencies for platforms to provide with greater transparency and control from brands and agencies. Based on shared product roadmaps and user-spotted UI additions, Google and Meta have begun rolling out updates in response to some of the feedback. New and potential future PMax features include negative keyword targeting, campaign-level brand exclusions, and options to disable certain autogenerated creative. Both Google and Meta have also indicated that the option to opt-out of buying on non owned-and-operated (O&O) channels is on its way. For Google, non O&O equals the Google Display Network (GDN) and Google Search partner network. For Meta, that’s their Audience Network.

In my opinion, being able to exclude non-O&O inventory is particularly important for increasing product appeal as it allows advertisers to exclude lower quality long-tail placements (e.g. MFA sites). Going back to the importance of operational efficiency, being able to sidestep the time/effort required to curate quality from the open web is likely appealing to many advertisers.

Implications

If black box bidders do become a fixture for the next phase of digital advertising, they’ll certainly contribute to a number of related industry shifts. In my opinion, a few of these include the growth of econometric modeling for measurement, best practices around bidder enrichment using 1st party/customer data, and changes in the roles and responsibilities of programmatic/biddable traders. We’ll aim to cover these topics in future posts.